A “Collection without Order”:

Implications and Applications of LEOcode

Martin Kemp

Leonardo’s drawings and manuscripts are notably diverse, and seemingly disordered. A minority of the surviving sheets were originally separate, some remaining so. Other sheets were extracted from codices. Some, like the Codex Arundel, were bound into volumes by later owners. Some were gathered together by Leonardo himself, folded and interleaved as ‘codices,’ maybe secured by stitching. The Codex Leicester is of this type, but probably not stitched by Leonardo. Some sets of sheets may have been more loosely aggregated in his workshop. There are also smaller, bound volumes, which served as convenient notebooks of a portable kind. A few of these have survived in something like their original form. Over the centuries much more has been lost than survives, and those pages and volumes that do survive have been dispersed, sometimes disbound and sometimes re-bound—and disbound again. A good number of sheets have been trimmed or cut up.

Putting the surviving papers into some kind of order has been a central task of Leonardo studies. Achieving this has been complicated by Leonardo’s own procedures in which the unities he discerned in diverse branches of human knowledge run counter to our later classification of ‘disciplines.’ On his own behalf in his later 50s, he became increasingly aware that his fluid modes of thought were not resulting in a workable order. On the first page of the Codex Arundel, a major focus of the present study, he confessed:

This will be a collection without order drawn from many pages that I have copied here, hoping to put them in order in their places, according to the subjects with which they will deal, and I believe that before I am at the end of this, I will have to repeat myself many times.

On the verso of the second folio in the Codex Leicester, our main focus here, he pauses along the way to warn:

I shall omit here the proofs that will be presented afterwards in the ordered work, and I shall pay attention only to find cases and inventions and I shall note them successively as they present themselves, then I shall give an order by putting together those of the same kind; therefore, for now, you will not wonder nor will you laugh at me, reader, if here such big jumps are made from one matter to another matter.

Historians’ ordering strategies have inevitably concentrated on content and style, attempting to map the intricate journeys of his intellect and creative imagination in relation to the documentation of his roving life: Vinci, Florence (twice), Milan (twice), Rome, and Amboise. An important technical dimension in recovering Leonardo’s original procedures has been what we may call the “archaeology” of the surviving papers, which helps reconstruct how the sheets were once assembled in series. We can track marks that are common to different sheets, including: blots, smudges, and stains transferred from one page to another; off-printing in which chalk or moist ink is impressed on a sheet above or below; indented or incised lines that are impressed on a sheet below; marks of the points of compasses that have penetrated to a sheet below; and not least, evidence of old stitch holes at specific intervals along the edges or down the central fold of sheets. And there are watermarks, long recognized as playing a key role in identifying batches of paper produced in various places at various times. Watermarks are the smallish logos modelled in wire and attached to the porous screen of the papermaking mold used to dip into a vat of suspended paper pulp. The translucent watermarks, visible when the paper is held up to the light, serve mainly to identify the name or geographical location of the paper maker.

Large databases have been produced, traditional and digital, beginning with Charles-Moïse Briquet’s monumental Les Filigranes in 1907, based upon the hand-tracing of 40,000 examples. Watermarks have been very useful, not least in the history of books. Nonetheless, with drawings and manuscripts it has often proved difficult to identify precise matches, especially since similar watermarks have appeared over long periods and wide geographical distributions.

The Current Initiative

The new techniques applied here allow the precise matching of watermarks after the filtering of visual interference that obscures them. In this case, the visual “noise” that is being virtually removed to produce an enhanced image consists largely of Leonardo’s writing and drawings! This conforms to my maxim that one researcher’s noise is someone else’s data. Selected geometrical points on the cleaned-up transmitted light images are used to precisely compare dimensions using ratios, which accommodates images captured with different resolutions. Even more compellingly, watermarks can be animated to fade one into another to disclose even slight divergences. This also acknowledges that the inherent “close looking” skills of Leonardo scholars can be accessed to confirm moldmates visually, rather than relying on data alone.

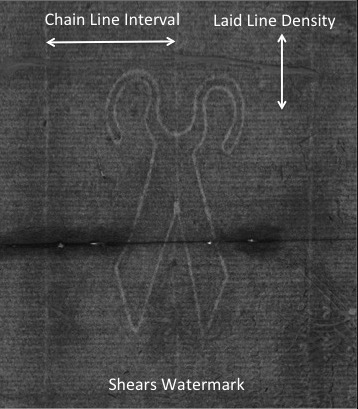

The “de-noising” also clarifies the grid pattern of the chain and laid lines in the original mold (see fig. 1). In the past, the patterns of these lines have been useful to a limited degree, in that their appearance seemed less specifically informative than watermarks. The new analytical techniques have totally changed the potential of the chain lines and laid lines. The chain line intervals and the relative density of the laid lines across the mold can be measured and matched across sheets of paper. The technique is like the use of fingerprints in a forensic investigation. Using the new visual data, it is possible to determine which sheets have come from exactly the same molds. These are defined as “moldmates.” Since two molds are used in alternate succession by the vatman, a second set of strained papers also having matching characteristics can be detected. These are called “twins” (fraternal not identical).

Figure 1: A de-noised image of a scissors watermark, indicating the locations of chain line intervals and laid line density.

We are now equipped to look at a series of papers, say the 18 double sheets of the Codex Leicester, to determine which ones came from the same batch. We can also look at other sheets and sets of sheets, such as those in the Codex Arundel, to see if any of them originated from the same place at the same time.

Moldmate matches imply a common place of origin and a narrow period of production: either from the same production run (days to weeks) or at some point during the lifetime of that one mold (nine months to two years for a popular size). When deciding between these two possibilities, it is the arrangement of the moldmates and twins relative to each other that is critical. When moldmates and twins (that are themselves moldmates) occur in close sequence, it may be deduced that the papers are from the same ream and, therefore, date from a narrow period of time (days to weeks). Isolated moldmates found out of sequence can only be dated to a broader, but still well defined, period of time (the lifetime of that particular mold).

In making such judgements, we need to take various factors into account. The first is the length of time an individual mold would survive its strenuous use by the paper makers. It has been suggested that the mold might last for two years, but this seems rather long when we consider that a mold might have been used to make hundreds of sheets each day. The second is the intermittent use of a mold over time to produce limited quantities of a particular kind of sheet, which means that the mold might have survived longer. The third involves the rate of turnover of the supplier. It might have been that some moldmates and their twins sat on the supplier’s shelves for some time, while others from the same production run had already been sold. The fourth is the purchasing practice of the user. If only a month’s supply was purchased at a time, matching sheets would probably be used across a narrow band of time. Buying (say) a three-year supply, which was stored in the artist’s workshop, weakens the precision of assumptions we can make. The fifth, which is notably imponderable, is the practice within the artist’s workshop. Were the papers neatly stored and used in a tidy sequence, or used in an erratic manner? With Leonardo, we face the added complication that he often seems to have progressively added script and/or images to a given sheet over a wider span of time than would be customary.

We can use our imaginations to paint a fictional picture of Leonardo’s workshop with untidy piles of paper on every available surface. In a single pile, we might find a few sheets filled on both sides with elaborate drawings and complex writings. We might notice a single drawing in the middle of a sheet. Or a few words. A memorandum or two. The costs of domestic provisions. Might there be some blank sheets ready for when he returns to that pile? Are piles roughly classified—anatomy here and weaponry there? But they are probably not systematic. Does he riffle through the piles impatiently looking for a mislaid sheet? Does he brusquely ask Francesco Melzi to help? “This is without order,” he complains. “Tell me if anything were ever done” (Dimmi se mai fu fatto alcuna cosa), as he writes on a number of occasions.

Or, the workshop is the very picture of order, everything in its due place, with the blank papers carefully stacked to be used one after the other. We see systematically arranged stacks of different types of paper, primed and unprimed. When a set of drawn and written papers has reached what seems to be its final form, the folded sheets are placed in cardboard covers, duly labelled and perhaps stitched. We do know that some of his sets of papers were labelled, such as the ‘Libro A’ cited a number of times in the Codex Leicester. Bound notebooks and his library are neatly stored in wooden trunks as we know. On multiple occasions, he listed books he owned, written by himself and other authors, including ones in store.

Instinctively I think most of us would favor the more chaotic picture. The truth probably lies between the two extremes. When Leonardo moved the base of his operations from city to city, some kind of ordering would have been expedient.

In assessing the new evidence presented about the sheets of paper used by Leonardo, our implicit or explicit assumptions about his working habits will affect the conclusions we draw. Bearing the various complications in mind, let us look in a provisional way at selected aspects of how the new evidence can contribute to our understanding of the Codices Leicester and Arundel.

The Codex Leicester

We have argued in the recent edition of the codex that it has been assembled from an outer set of seven sheets and an inner set of eleven sheets, with the implication that the outer set was compiled somewhat earlier. The evidence involves content, format, inks, handwriting, and the ‘archaeology’ of the sheets. It is supported by the fact that Leonardo’s retrospective counting of topics at the top of the pages is only conducted for the inner set. The topics of the impact of sunlight on the earth and moon, and the earth-like nature of the moon (with its supposed seas), are found only in the outer set. The discussions of water in and on the ‘body of the earth’ in the outer set is shared across the two sets, but the pages in the outer set are generally more varied in layout, compared to the dense blocks of text with marginal illustrations and notes in the inner set. However, at first sight the layout of the bi-folio 2v-35r could easily be transferred to the inner set, but the other side of the bi-folio (2r-35v) is laid out quite loosely and contains discussions of astronomical matters.

The difficulty of generalizing and reaching secure conclusions is shown by folio 4r, which contains a sustained analysis of the blue color of the air and of smoke, a topic which stands to the side of the main themes of the codex and is out of keeping in format with the other three pages of the bi-folio. It has also been suggested that the original order of the outer sheets was 1-2-7-3-4, with 5 and 6 later introduced and 7 moved. It is also apparent that the notes and drawings on some of the pages were completed over a period of time. “Archaeological” and other evidence indicates that he wrote and drew on the sheets when they were open as bi-folios and also when they were folded, sometimes folded in reverse. There are signs that he also added items to sheets after they were interleaved. The experimental water tank sketched on 29v relates to a note squeezed to a corner of the next sheet, 30r, which otherwise involves astronomy and clearly belongs with the early folios of the outer set. The same glass-sided tank is discussed and illustrated twice in the margins of 9v.

How does this complex picture work with the new “coding” of watermarks, chain line intervals and laid line densities? The full digesting and correlation of the bodies of evidence will take some time and requires data from other collections. But we can make some initial observations.

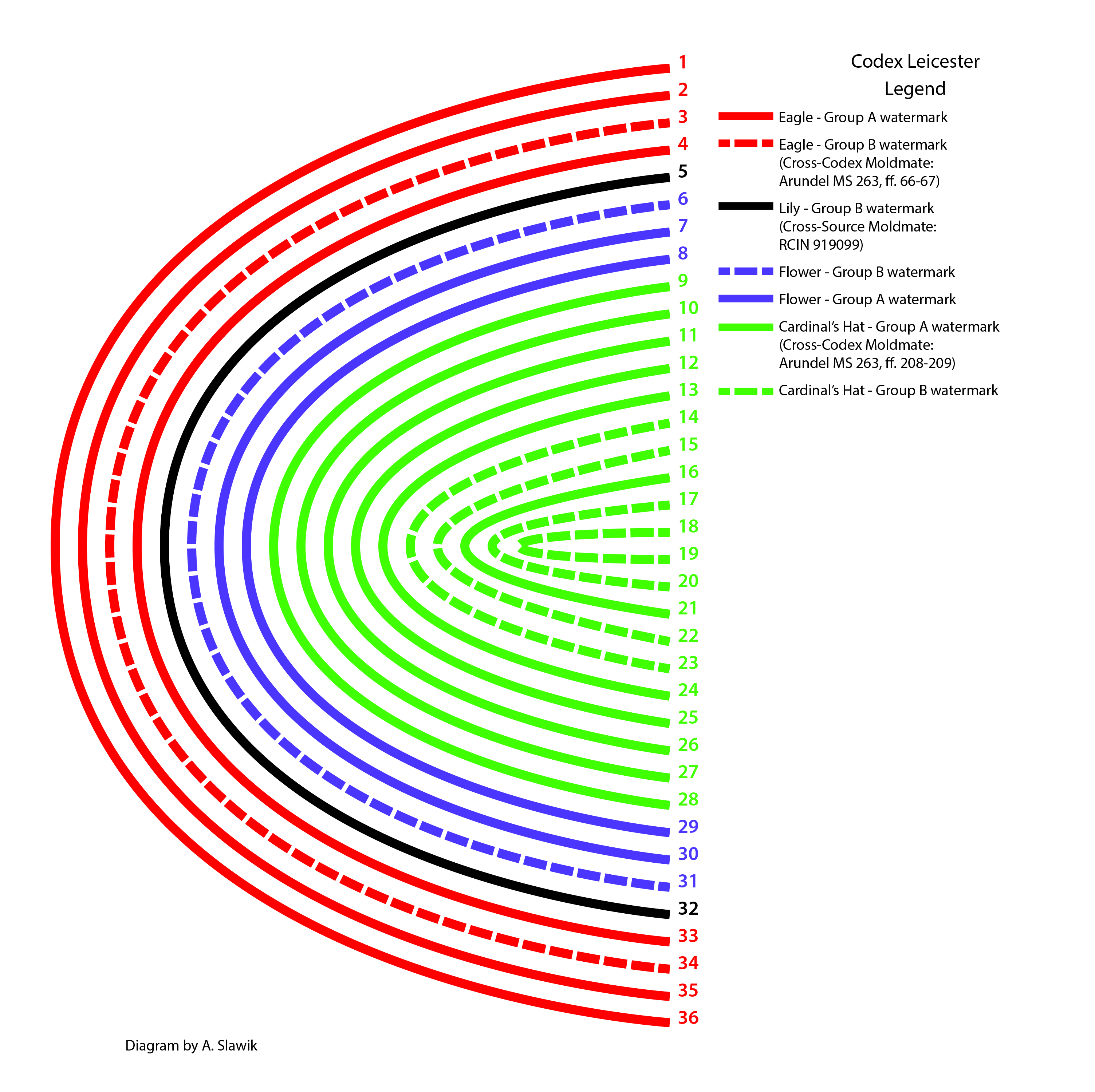

Figure 2: Collation chart of the Codex Leicester (Diagram by A. Slawik).

At first sight, the new findings work well with the inner and outer sheets hypothesis. Sheets 9 to 13 and 16 are moldmates and share identical cardinal’s hat watermarks (Group A), while sheets 14, 15, 17 and 18 share the cardinal’s hat (Group B) watermark and are probable twins. In the outer set, sheets 1, 2 and 4 share an identical eagle watermark (Group A), while sheet 3 with a Group B eagle watermark is a probable twin (see fig. 2).

Sheet 5’s fleur-de-lys watermark [elsewhere on leocode.org referred to as lily (heraldry), in accordance with English language watermark from the International Association of Paper Historians] is unmatched elsewhere in the codex. Its folios are varied: 5r, which is heavily filled, deals with water, reflections and light on the moon; 5v treats the impact of water in a kind of list; 32r, also on water, is ill-organized and incomplete, while its verso contains blocks of notes on water added at two or three different times. The uneven nature of sheet 5 supports our idea that it was inserted into existing sheets of the outer set. Sheet 6, devoted to sustained discussions of water and rivers, with a flower watermark (Group B) is also unique, and shares many of the characteristics of the inner set, which supports the idea that it was also added in a second phase to the outer set, as Leonardo strove to give some shape to his arguments.

It is with sheets 7 and 8 that things become difficult. Folio 7r focuses on optical aspects of astronomy with a short added note about bridges and dams, while the verso begins with ‘veins of water’ in mountains before passing to astronomical optics. Folio 30r of sheet 7 also discusses optical astronomy in some detail with a squeezed-in note about water, including his experimental tank. The verso contains two or three phases of untidy notes about water in motion. It looks as if it belongs with the outer set. Sheet 8, on the other hand, discusses aspects of the behavior of water on densely written pages with neat margins and little or no illustrations, as is wholly characteristic of the inner set.

But sheets 7 and 8 are moldmates!

Having been formed from the same papermaking mold, they are therefore intimately associated. There are two obvious but different explanations. Either the two sheets became separated in Leonardo’s workshop to be used at separate times and only coincidentally did the two moldmates end up one after the other. (It should be noted that moldmates are not immediately apparent to the naked eye, nor would there be a reason to deliberately scrutinize and select one). Alternatively, the concept of the inner and outer sets falls into question. It is possible that sheet 8 is the first to mark a revised strategy, which might have been introduced during his filling of the pages, in which case the concept of inner and outer sheets might be reconciled with more or less continuous activities across the sheets. At this early stage, there is no ready way of deciding. We will return to this conundrum.

The Codex Arundel

The Codex Arundel is very different in that it was compiled from a variety of manuscript bi-folios and separate pages. Named after the 14th Earl of Arundel (1585-1646), a major collector, it comprised 285 sheets, dating from various phases of Leonardo’s life. On the first page, preceding the note that “this will be a collection without order…”, he recorded that it “was begun in the house of Piero di Braccio Martelli on the 22nd March 1508.” At that time, he was shuttling between Florence and Milan, trying to satisfy the demands of the Florentine government and the French rulers in Lombardy. The sheets to which Leonardo’s memorandum apply have been seen as the first 30 folios. However, a clear homogeneity of content only extends as far as folio 18v, involving basic mechanics, weights, balances, pulleys and centers of gravity. Folios 19r–30v cover a number of different subjects, of which the most frequent is water, much in the style of the Codex Leicester, which dates from a similar period. There are also some folios devoted to issues of reflection from spherical bodies, which relate to the light of the moon. The diagram of the foliation shows that it was assembled with a degree of improvisation.

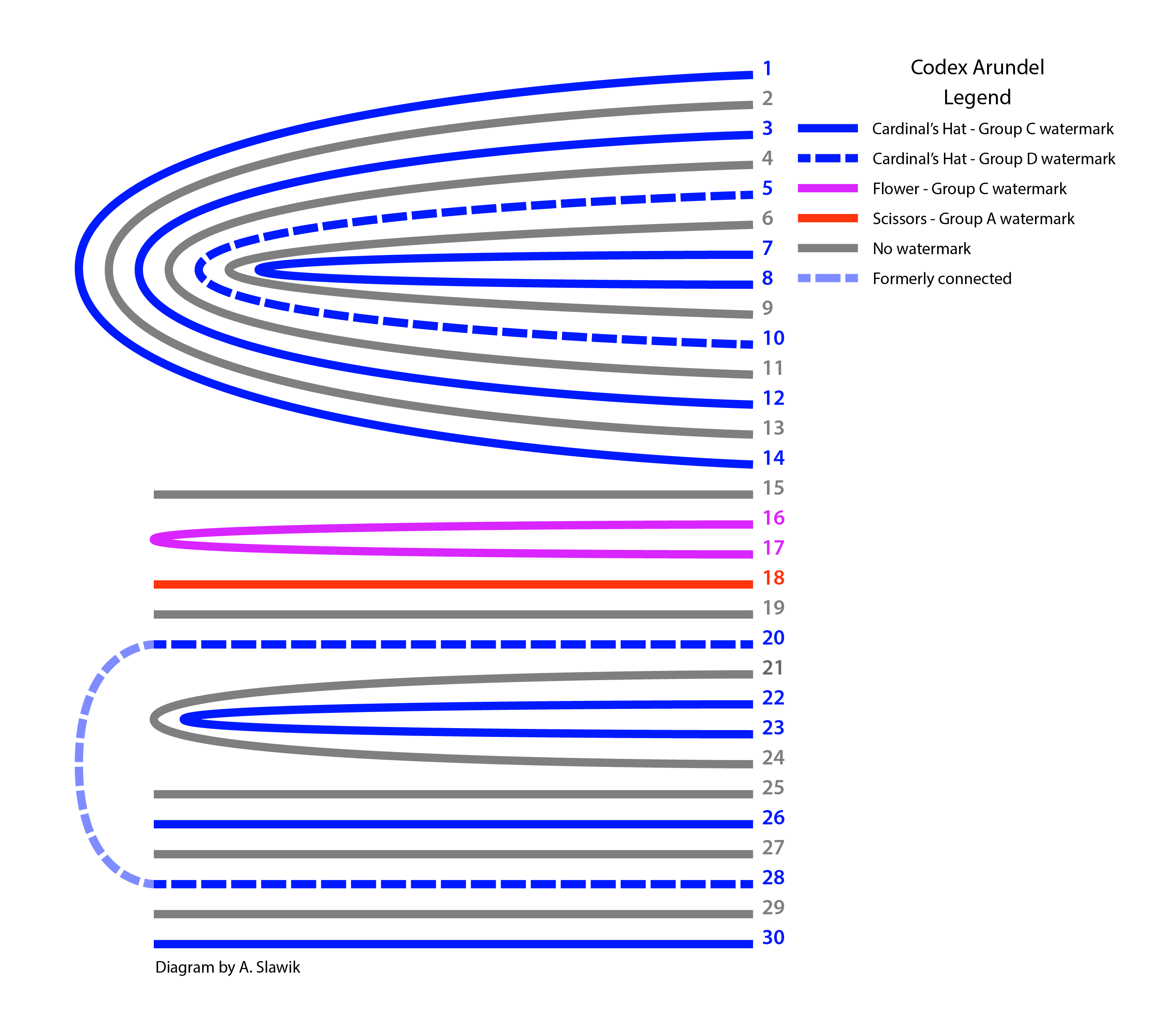

Figure 3: Collation chart of the Codex Arundel, ff. 1-30 (Diagram by A. Slawik).

The moldmates shared between the two codices do not involve the first 30 folios of the Arundel. The match for the Eagle B watermark of Leicester 3 is with Arundel ff. 66-67, which discusses balances, as in its earlier folios, and has no obvious connection with Leicester. The cardinal’s hat (Group A) watermark on Leicester sheets 9 to 13 and 16 finds moldmates in Arundel ff. 208-209, but these folios deal with geometrical matters and have no obvious link with the contents of Leicester. Or, at least, the link is not apparent to us.

There are two possible explanations of this lack of obvious correspondence of content between moldmates. The most likely is that the molds having a cardinal’s hat or an eagle watermark continued to be used for as long as the molds themselves remained viable. What we see is Leonardo procuring locally manufactured reams of paper circumstantially containing the products of one long-lived mold. The other is that the order in which Leonardo used sheets of paper from various batches was extraordinarily unsystematic as his mind moved so rapidly from topic to topic that he would, for instance, be writing about water, when a loosely related question about balances intruded, and the next piece of paper was taken up to deal with the new topic. It may be that both explanations are right.

These are early days for the present mode of analysis, and the data embraces only a few of the thousands of pages that survive. The watermark for each watermarked sheet in the Royal Collection at Windsor has been recorded, and these await integration into the wider project. The more data we collect, the more reliable will be the results of the analyses. We should be able to reunite sheets that have become widely separated after they left the hands of Leonardo and later of Francesco Melzi, the aristocratic pupil who was guardian of his master’s legacy.

As we proceed, it may become evident that we are missing some obvious tricks in how we use the evidence. We hope that other holders of Leonardo’s works on paper will participate—to extend the scope and value of the project as a whole and for the benefit of their own collection!

It has taken the discipline of art history a long time to judge how data from scientific examination can be integrated into the wider body of historical evidence—a task that is still very incomplete. The techniques themselves can be developed further, above all the matching of laid lines, which is currently limited to rather basic density matches. More data, in quantity and precision, may allow us to chart damage to the wire screens and the accompanying watermarks, much as we can witness the progressive wear of punches used to decorate gilding in Medieval and early Renaissance panel paintings. It seems very likely that artists who used paper less erratically than Leonardo will present subjects for study that involve fewer puzzling variables.

The new evidence makes new demands on our understanding. The matters of detail that are involved may seem to concern minor puzzles of specialized codicology, of little wider consequence. But the detailed observations of Leonardo’s folios help us disclose how this most extraordinary of minds worked – not least how he could keep more than one stream of thought running contemporaneously. Identifying moldmates, as we have seen, may well bear witness to how he switched attention from subject to subject with astonishing fluidity. They also illuminate how he strove (with limited success) to find a way that the streams might flow in an orderly manner, so that they might be accessible to others. Modern tools beyond even Leonardo’s imagining are allowing us to move closer to realizing Leonardo’s aspiration to create bodies of visual and conceptual knowledge that unite rather than separate the manifold operations of nature. But we have a long way to go.

Note on Sources:

For illustrations and transcriptions of Leonardo’s manuscripts, including the Codex Arundel, see https://www.leonardodigitale.com.

For the Codex Leicester, see Domenico Laurenza and Martin Kemp, eds., Leonardo da Vinci. A New Edition of the Codex Leicester of Leonardo da Vinci, 4 vols. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2019/2020. https://www.oxfordscholarlyeditions.com/view/10.1093/actrade/9780198832874.book.1/actrade-9780198832874-book-1?rskey=GyM68k&result=1.bbb.

Paolo Galluzzi, ed., Water as a Microscope of Nature: Leonardo da Vinci’s Codex Leicester. Florence: Giunti, 2018.

Juliana Barone, ed., Leonardo da Vinci: A Mind in Motion, exh. cat. London: The British Library, 2019.